Belly of the Beast

Copyright Cleveland Clinic

The Cleveland Clinic has long been an epicenter of development and institutionalization of gynecologic practices in the United States and worldwide. In a recent blog from the Cleveland Clinic’s website, hysteropexy and hysterectomy for treatment of vaginal prolapse were compared.(1)

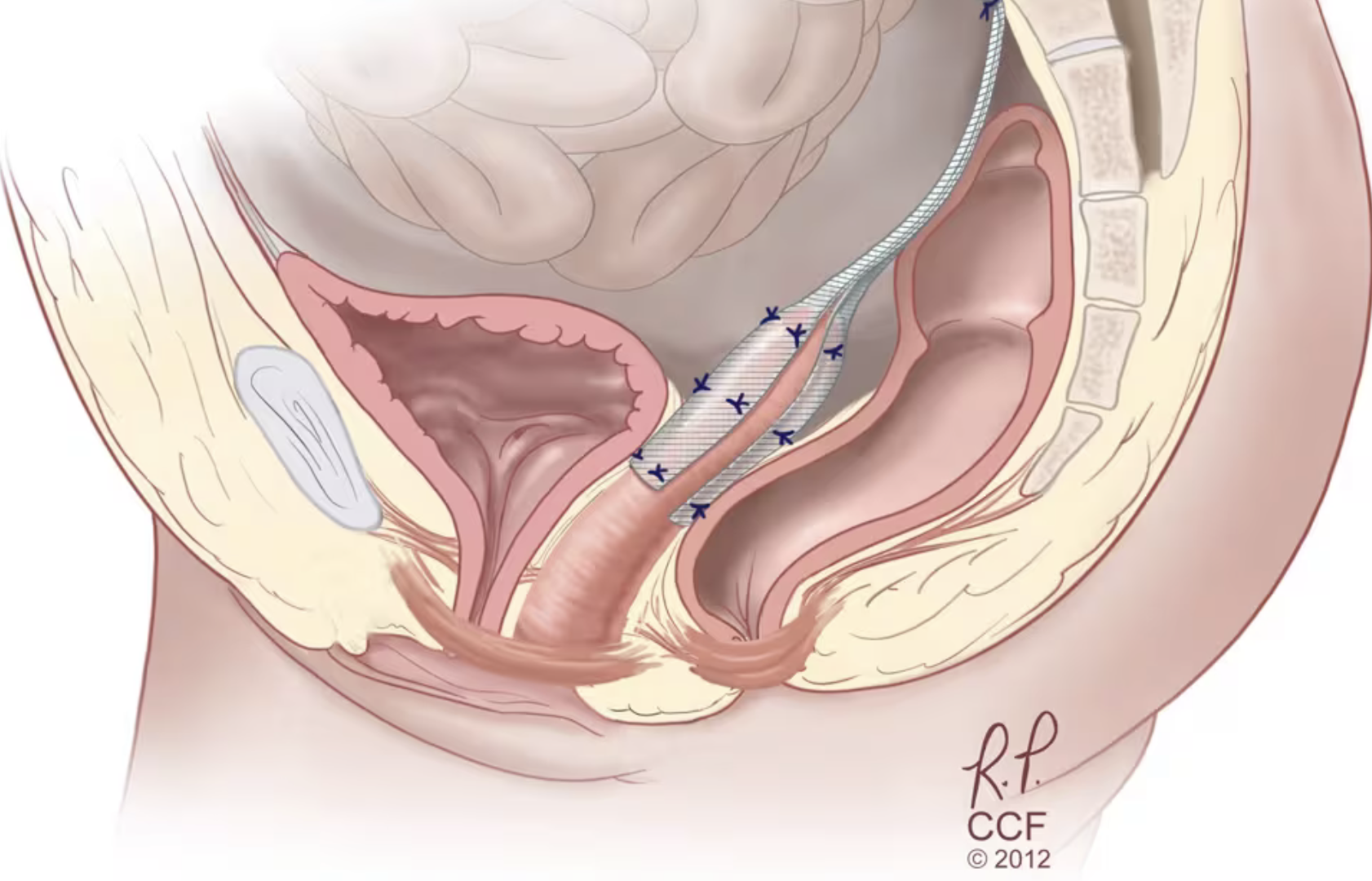

Although unstated, the authors used the term “hysterectomy” to actually describe sacrocolpopexy, a deep abdominal surgery (now performed robotically) in which the post-hysterectomy vaginal stump is attached to the anterior ligament of the spine by way of a polypropylene mesh bridge. This surgery is routinely performed to prevent or treat vaginal vault prolapse and vaginal evisceration.

In much the same way, hysteropexy, or more accurately hysterosacrocolpopexy, attaches the cervix via mesh to the sacral spine, a surgery often sold as “uterus sparing” and “minimally invasive”.

The authors state, “Modern hysteropexy techniques for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) have been around for nearly two decades and have built a solid track record of improving function and patient quality of life.”

Cleveland Clinic’s Amy Park MD tells us, “People shouldn’t think that they can’t have their prolapse repaired if they really want to retain their uterus. They can, and they may have better outcomes with hysteropexy”.

Dr. Park go on, “Hysteropexy stacks up well against hysterectomy in effectively treating prolapse repair.”

Yet these statements are immediately followed by glaring contradictions pointing to the actual facts of the matter.

“Prolapse recurrence rates are pretty similar between the two, and even a little better with retaining the uterus, although not by a lot.”

In quoting a 2016 study, “…the two groups provided a similar anatomic cure, although the hysterectomy group experienced greater subjective cure and quality-of-life improvement at mean follow-up of 33 months.”

Let’s understand what is really going on here.

Sacrocolpopexy, a deep and dangerous surgery, was developed solely because hysterectomy often results in profound vaginal vault prolapse. Many complications are associated with the surgery, including stress urinary incontinence with or without a prophylactic continence procedure, recurrent cystocele, mesh erosion into the vagina, infection, bowel dysfunction, severe hemorrhage, sacral osteomyelitis (bone infection), and death.(2-6)

The durability of the operation decreases over time, which is likely related to the fact that the anterior ligament of the spine undergoes age-related changes:

“Its energy-absorbing and elastic properties decrease with age, as does the strength of the bone into which it is attached. As the mineral content of the surrounding bone decreases with age, the strength of the ligament also decreases.(7)

During the procedure, the sacrum must be dissected from the connective tissues that envelop it, and the sacral artery identified and carefully avoided. One surgeon describes the consequences of accidentally cutting into the sacral artery:

“The potential for significant hemorrhage that is almost impossible to stop exists with this approach. If major bleeding occurs, hemostasis by suturing is almost impossible. Usually pressure for 10-15 minutes stops the bleeding. If this does not work, a sterile thumbtack with bone wax nailed into the sacrum works.” (8)

Many women lost their lives on the operating table as doctors were getting up the sacrocolpopexy learning curve. How many still die from the robotic form of the operation is unknown.

Hysteropexy carries the same surgical risks as sacrocolpopexy, with the added risk, in the event of future hysterectomy, of great difficulty dissecting the deeply embedded mesh from the lower spine (9).

More egregiously, the operation is often said to improve sexual function, which is an anatomic impossibility.

The cervix is continuous with the uterus, which in normal anatomy is positioned against the lower abdominal wall. During sexual intercourse, the penis pushes the cervix all the way forward, a necessarily pleasurable sensation for both men and women. After hysterectomy, there is nothing for the penis to push against, a tragic fact completely concealed by gynecology, but not lost on men.

Far more horrifying, after hysteropexy as the penis pushes the cervix forward, the cervix is yanked off its surgical underpinnings at the second sacral vertebra.

Hysteropexy is an anatomically misconceived operation in general, and perilously so in the sexually active woman.

Maher CF Murray CJ Carey MP Dwyer PL Ugoni AM (2001). Iliococcygeus or sacrospinous fixation for vaginal vault prolapse. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 98(1): 40-4. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01378-3. PMID: 11430954.

Baessler K Schuessler B (2001). Abdominal sacrocolpopexy and anatomy and function of the posterior compartment. Obstetrics & Gynecology 97(5 Pt 1): 678-84. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01205-9.

Drutz HP Cha LS (1987). Massive genital and vaginal vault prolapse treated by abdominal-vaginal sacropexy with use of Marlex mesh: review of the literature. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 156(2): 387-92. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(87)90289-4.

Kohli N Walsh P Roat T Karram M (1998). Mesh erosion after abdominal sacrocolpopexy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 92(6): 999-1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0029-7844(98)00330-5.

Morley GW. Treatment of uterine and vaginal prolapse. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 39(4): 959-69. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199612000-00024.

Vleeming A et al (1999). Movement, Stability & Low Back Pain - the essential role of the pelvis. Churchhill Livingstone. P.12.

Underwood PB (1998). Been there — Done that: Surgical challenges. Americal Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 179(2): 330-335.

Maher CF Carey MP Murray CJ (2001). Laparoscopic suture hysteropexy for uterine prolapse. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 97(6):1010-4. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01376-x.